This blog post by Sam Bridgewater gives some background to the natural capital valuation approaches used in PACCo to assess the environmental and socio-economic value of estuary restoration work (see the full reports on the downloads page here – reports section of the PACCo website). We have used natural capital approaches to help us to assess the value to society of carrying out this scheme, and this information is likely to be helpful for other estuaries who are interested in carrying out estuarine habitat restoration or managed realignment.

Initiated in 2001, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was launched by the United Nations to assess the consequences of ecosystem change globally for human well-being. The findings provided a detailed scientific appraisal of the condition and trends in the world’s ecosystems and the services they provide to society. This includes the provision of clean water, food, forest products and flood control.

Although the study highlighted that some of the changes that have been made to the world’s ecosystems have contributed to substantial gains in human well-being and economic development, these gains have frequently been achieved at growing costs to the environment and have been accompanied by a degradation of the ability of the planet’s natural systems to support society into the future. All too frequently, when economic decisions are made, the value of the natural world is not included, with many ecosystem services ignored or given a default value of zero. This can lead to perverse long-term outcomes for society. For example, if we consider a hypothetical forest on a hillside, there is value in the timber that could be extracted from it. However, such a decision to fell the trees may not have factored in the flood protection function of this forest to communities that may lie below. The cost of repairing any subsequent flood damage, or installing artificial flood protection in replacement of the trees, may subsequently far outweigh the original value of the timber extracted. If this is the case, was it a good decision for society to fell the trees in this instance? Likely not.

Estuary environments are important in the storage of carbon

There are various ways in which nature can be valued. Typically, society takes a utilitarian (anthropocentric) concept of value with ecosystems valued for the services they provide to us from their use, either directly or indirectly (use values). However, for many people, nature also has an intrinsic (non-use) value.

The focus estuary restoration sites of the Promoting Adaptation to Changing Coasts initiative (PACCo) initiative are in the lower Otter Valley in East Devon, England, and the lower Saâne Valley in Normandy, France. Both are relatively small estuaries and share a number of similar characteristics and challenges. Restoration works are now nearing completion at both sites with the final financial cost of restoration to society being significant. For any significant climate adaptation scheme it is important to know whether it has provided ‘good value for money’ and what the benefits and disbenefits might have been. It is important that society learns from what has worked and what hasn’t. Learning is an important part of PACCo and the two restoration sites provided a perfect opportunity to demonstrate how valuations related to ecosystem service delivery can be undertaken.

For both projects a utilitarian approach to valuation was taken with a natural capital approach followed. Natural Capital is defined as ‘….elements of nature that directly or indirectly produce value or benefits to people, including ecosystems, species, freshwater, land, minerals, the air and oceans, as well as natural processes and functions.’ (Natural Capital Committee 2014). This approach accepts that the environment is clearly ‘multi-functional’ and delivers a range of environmental, social and economic benefits to society. As far as it is possible to do so, it also attempts to recognise these functions, assess their importance and place a financial value on them, although this final stage is often difficult to do. In the case of estuaries, for example, estuarine habitats sequester carbon, protect against coastal flooding and reduce water quality problems, as well as providing quality space for recreation and biodiversity. A natural capital valuation should not be considered as the only lens through which to view the value of a restoration project, but as a useful process to understand the benefits and disbenefits of such schemes.

A natural capital valuation can be either qualitative or quantitative. A qualitative approach was followed for both the lower Otter and Saâne Valleys with a quantitative study conducted for the lower Otter valley only. The value of a qualitative assessment is that it is quick, cheap and easy to conduct and a wide range of ecosystem services can be assessed. It can provide a useful summary and overview of the benefits provided by the natural environment. It can be useful at drawing attention to key services and highlighting those that should be the focus of more detailed assessments. This kind of study is perhaps most useful at the early design stage of a scheme and can be useful in communicating the anticipated pros and cons with stakeholders.

Quantitative modelling is more reliable, accurate and can be standardised but is only as good as the data upon which it is based. For a quantitative assessment, only a relatively small number of ecosystem services can be valued monetarily. Financial values can be based on a variety of market, use and non-use valuation techniques, often based on transferring values from other studies. Such an approach is important at highlighting the values of the natural environment that are often hidden, or assumed to have zero value.

So what are the broad conclusions of the studies for our two sites?

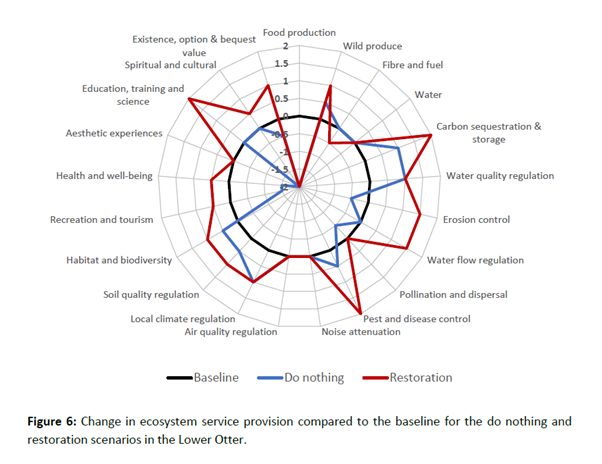

For the qualitative study in both locations the ecosystem services being delivered by the baseline (pre-restoration situation) were first assessed, before assessing the predicted delivery of ecosystem services under both a do nothing scenario and a restoration scenario. Cultural services (e.g. support of health and wellbeing and aesthetic experiences) were important at the sites prior to restoration, with both sites already attracting considerable numbers of visitors. Regulating services (e.g. climate and soil regulation) were generally of low importance, apart from habitats and populations for biodiversity which were considered to be of moderate significance. Production services (e.g. food production) varied between the sites, being low in the Saâne Valley, but more mixed in the Lower Otter, with food and water production being significant or very significant in the latter.

Under a ‘do nothing’ scenario cultural services were predicted to fall markedly at both sites, primarily due to a forecasted major drop in visitor numbers caused by uncontrolled flooding impacting the visitor experience. On the other hand, regulating services showed some difference, with the same or lower delivery for most services predicted in the Saâne Valley, with the exception of habitats for biodiversity which is predicted to fall significantly. In the Lower Otter, regulating services were predicted to show a much more mixed response, with a number increasing in delivery, along with several that stayed the same and a few that are expected to decline. Amongst the production services, a similar response was predicted at both sites, with food production expected to fall, but other services generally similar to the baseline.

Responses under the restoration scenario were similar at the two sites, with increases in cultural services and increases in a number (but not all) of the regulating services. Habitat for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, water quality, water flow and soil quality regulation are amongst the services that are expected to be enhanced considerably by the restoration projects and will deliver significant or highly significant benefits at both sites. Food production is predicted to fall, whereas wild produce will increase slightly at both sites, with little change in other production services. For the quantitative analysis a baseline scenario was chosen whereby the existing situation continues for 15 years, before an unmanaged breach occurs, although in reality, the risk of this occurring sooner would be high. With the Lower Otter Restoration Project it is important to point out that the project’s intertidal habitats are being created as (coastal squeeze) compensatory habitats to enable the Environment Agency to continue to manage flood risk for thousands of properties in the Exe Estuary. The net benefit of this has previously been estimated at over £350 million. Thus, substantial additional off-site benefits result from LORP being implemented, which could not be included in the assessment. The qualitative study concluded that, over 60 years, the gross natural capital present value of the ‘baseline’ scenario is £23.6 million compared to the restoration scenario of £35 million. Thus the natural capital benefits associated with the restoration are therefore substantially higher (50%) than those calculated for the baseline scenario. Of the benefits which could be monetised, the benefits related to the welfare value of recreational visits were valued most highly, followed by physical health benefits, water quality and carbon sequestration related benefits.

These results are important both for the two participating estuaries, and for other estuaries interested in or looking to implement managed realignment and estuarine habitat restoration – showing that overall the benefits to society far outweigh the costs of implementing such a scheme.

The full natural capital report on the Lower Otter is available here; and the qualitative report will also be available shortly in the reports section (downloads page) of the PACCo website.

https://www.pacco-interreg.com/