This summer, after 15 years of planning and an immense collective effort, a breach will be made in a flood embankment in the lower Otter valley. This will allow the tide to ebb and flow several kilometers inland much as it once did several centuries ago before the valley was drained. Just make a breach and let the sea in! It sounds so simple, doesn’t it!

For millions of years our coastlines have been subject to natural change due to the eroding power of the sea. For thousands of years human activity has also altered coastal areas. Settlements and sea defences have been built, wetlands drained and reclaimed for agriculture and infrastructure including roads, sewage treatment works, tips and recreational facilities placed in areas which were formerly floodplains. This has resulted in societal benefits but has come at great ecological cost, with these modified systems often unable to adapt to climatic changes. One thing is certain: many coastal communities will not be able to cope with the added pressures of the (minimum) 1 meter of sea level rise predicted for our coasts over the next 100 years.

The lower Otter valley covers only around 100 hectares of catchment. However, within its confines there are multiple climate adaptation challenges shared by coastal settlements around our shores. If we can adapt the Otter valley and show how this can be done and the benefits that arise, perhaps maybe other communities can take encouragement and follow suit? Doing nothing about climate change is of course always an option. But for many coastal areas it is unlikely to be an attractive one.

Starting the process of adaptation can be complicated. The problems can seem huge and insurmountable. At the final PACCo conference in February 2023 one of the speakers presented the following quote attributed to the pioneering aviator Amelia Earhart. The speaker suggested that this was relevant to practitioners of climate adaptation: The most difficult thing is the decision to act, the rest is merely tenacity. Reflecting back over the last ten years, this sentiment seems apt.

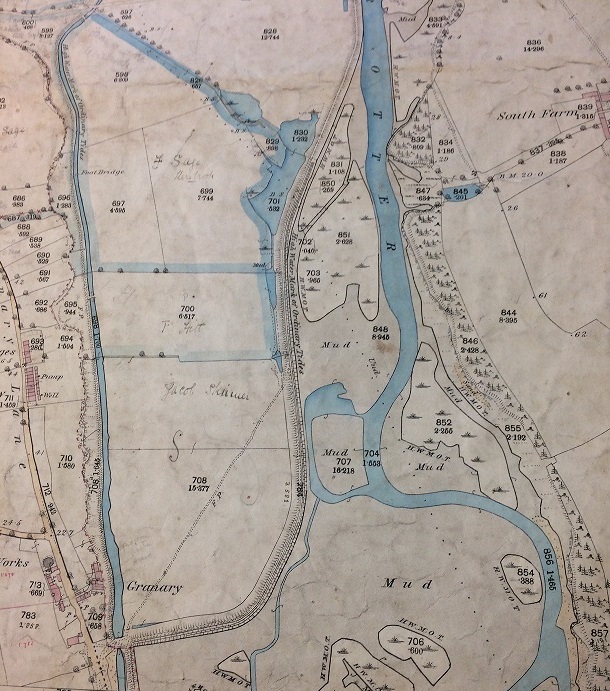

In 2009 Clinton Devon Estates commissioned a report on the flooding issues facing the communities that live within and around the lower Otter valley. Amongst the potential solutions presented by the ‘Haycock Report’ as it became known, was to reverse some of the modifications made to the valley over the centuries, to reconnect the river to its floodplain and to allow the sea back up the valley. In essence, this meant accepting that whether we liked it not, as seas levels rise, the tide will reclaim the land taken from it and that it is far better to manage this process than to wait for a catastrophic breach with unpredictable outcomes. The concept was simple enough. However, the journey of its delivery has been quite long (in human terms, although not in climatic / landscape terms) and at times a little fraught.

The first step was to understand the history of the valley, how it is currently used and valued by local society, the threats presented from sea level rise and climate change and the opportunities and risks that a possible adaptation project might present. This was when the partnership with the Environment Agency first began. Such an initiative needed skills and experience beyond those held by the landowner Clinton Devon Estates and its conservation charity, the East Devon Pebblebed Heaths Conservation Trust. The Environment Agency understands water, how it flows, its impacts on society and how it can be managed. They are leaders in coastal adaptation. Considerations pertinent to the Otter valley included: how is the land being used and how might farming activity be impacted both in the event of a managed or a catastrophic breach? How might a local cricket club in a floodplain be given a future? How might a scheme that recreates saltmarsh and mudflat impact on flood risk to houses and businesses locally? What is the current and future liability of a municipal tip prone to flooding? What wildlife might be lost and what gained by allowing the sea into the valley? Might tidal inundation impact on the supply of fresh drinking water? What might it mean for local infrastructure? Would roads and footpaths be flooded?

Over the next three years the first tentative steps were made in exploring and answering these questions as well as consulting with the local communities on the issues and potential solutions to problems, as perceived by them. In these earliest days the discussion were conceptual and it wasn’t clear for some years whether there was an actual ‘deliverable project’ hidden within the many adaptation ideas being floated. Indeed, it wasn’t until 2020 that we knew for certain that the project in its current form could proceed. There were times when considerable faith was needed to keep on going. In the earliest days a stakeholder group was established. This encompassed broad local interests and was incredibly important as a vehicle for communication and engagement and for capturing local concerns and hopes regarding the valley, and the impacts of flooding and climate change. This first phase of work culminated in the presentation of a number of future options for the valley to the local community in 2015. There was a clear preference at the Options Appraisal for the design that then went forward towards delivery.

There are a number of questions that must be answered in developing a project of this kind. Is it socially and environmentally desirable? Is it technically feasible to deliver? How much will it cost and who will pay for it? All of this work was taken forward in ever-greater detail over the following five years leading up to the planning application submitted to the local planning authority in 2020. This was unanimously approved by the planning committee. However, this is not to say that the project has always had full approval locally: far from it. The development and delivery of the scheme has at times been a bumpy ride. Although there are many who support it, there are also a significant number who disagree with its assumptions, its vision and / or the manner in which it has been delivered. During its delivery phase (2021-2023) there has been significant local disruption. At times the site has seemed like one enormous construction site with a much-loved pastoral landscape changed beyond recognition to be replaced with one of diggers, cranes and piles of earth, as the site has been re-scaped and its infrastructure adapted. Amongst the most painful periods was at the beginning of the construction phase when existing hedgerows, scrub and trees within the floodplain were removed. Many mourned their loss and the sense of grieving was keenly felt and as openly expressed. One of the most challenging aspects of the scheme – indeed of all climate adaptation schemes involving landscape scale change – is how to ensure progression with as much societal support as possible, accepting that this will never be universal.

The award of Interreg France (Channel) England funding in 2021 and the initiation of the PACCo scheme was a key milestone towards achieving the vision outlined in the Options Appraisal. This came after a failed attempt to attain Heritage Lottery Funding a few years previously, although the Interreg proposal was able to build on the work done for the original Lottery proposal. Additional funding to deliver the scheme came from the Environment Agency who became the lead partner in 2015. Their interest in supporting it was in the potential for the Otter valley to deliver compensatory habitat related to food defence works on the nearby Exe Estuary. These works are estimated to have a value to society of more than £350 million.

Not only was the project now financially feasible to deliver but the structure of the PACCo work packages meant that all of the learning resulting from the scheme could be captured and made available for other communities to benefit from. As part of the PACCo initiative the lower Otter valley partnered with the Saâne Valley in France. This valley on the Normandy coast experiences similar challenges relating to climate change; and those managing the site were advocating a similar approach of adaptation. This fresh alliance brought new partners, an international perspective and a deeper seam of learning to mine. This part of the scheme was also initially demanding, as multiple partners on both sides of the channel endeavoured to deliver shared outcomes and activities in two languages. And all this at the time of the Covid pandemic. Challenging, yes, but also richly rewarding as we learnt from one another about how best to proceed schemes of this kind. Many challenges arose but were finally overcome (through tenacity) as land holdings were restructured, complex ground and surface level water commissioned and infrastructure moved or adapted.

Those who have visited the Otter and Saâne valleys over the last two years will be most struck by the on-site changes: the building of a new sewage treatment works and the relocation of a flood-threatened campsite in the Saâne valley, for example, or the raising and moving of a road and the creation of a 30m road bridge under which tidal waters will pass in the Otter valley. However, behind the scenes very significant learning related to climate adaptation has been captured and placed in the public domain, which is all to be found on the PACCo website. This learning includes: how do you assess climate risk? How do you measure environmental, and socio-economic costs and benefits of adaptation? What is the best way to engage with the public? How do you go about carrying out climate adaptation?

This blog will be published before the Otter flood embankment is breached. At the time of writing the site still looks like a construction zone as attention focuses on the building of a 70m footbridge that will span the breach and ensure continuity of part of the South West Coast Path. After two years the local community and visitors may be tiring of the disruption. But the end is now within sight and even during this time of maximum disruption there is excitement in the air of the benefits to come and an early promise of an uplift in wildlife: the biggest flock of European white-fronted geese to be seen in Devon for decades; hundreds of snipe occupying the nascent creek network of the grazing marshes; numbers of black-talked godwit ten times greater than have been witnessed for a generation. Already, thousands of people are walking the new raised and improved footpaths on the west of the valley. For some who are less able bodied, this new infrastructure has provided the first accessible means to enjoy the valley. By the time this article is released the new raised road across the Otter valley will be open and the community and businesses of South Farm can move around untroubled by regular flooding. Three months from now senior and junior teams from Budleigh Salterton Cricket Club will play their first matches on their new ground which will look out over a tidal valley. Five years from now once the habitats have developed, we hope the site will be internationally recognized as a conservation area supporting many species of rare wading bird.

PACCO has been a wonderful project to be involved with. It hasn’t been an easy initiative to deliver but rare are the times in one’s career when one has an opportunity to learn so much, so quickly, and to be involved in contributing something tangible to addressing one of the most pressing issues of our time: climate change. I am an ecologist and as such my final words relate principally to wildlife. For several centuries the Otter Estuary has been the constrained and heavily modified supporting act lying between the Axe and Exe estuaries. Often overlooked by naturalists it has only shown glimpses of its former wildlife glory. Its invertebrate, fish and bird life were once magnificent before the valley was drained. They will be again.

Adaptation to climate change can be difficult – both the acceptance and the ‘doing’ of it. But I sincerely believe that addressing head-on the relevant problems, issues and concerns can bring multiple benefits for society and the environment. I hope that in due course the lower Otter valley will become a model for adaptation and environmental enhancement that can inspire others to carry out similar work elsewhere. Others can also learn from our mistakes.

Thank you to the Interreg France (Channel) England Programme and the Environment Agency for supporting and funding the initiative and making the vision for the two case study sites a reality. Thank you also to the many colleagues (now friends) who over a period of ten years have collectively developed and delivered the scheme, and to those from the community who have engaged with the process to make the project the best it could be.