It is natural towards the end of a project to become reflective and ask yourself whether you are happy with what has been achieved – did it exceed or fall short of the early vision and aspiration? Was the manner in which it was achieved acceptable and the best it could be? Could it have been done better, more easily, more cheaply? What would we have done differently if we had the time again? What risks didn’t we foresee?

There are many aspects to delivering climate adaptation at scale. One of these relates to the technical ability to deliver the project and understand and manage any associated risks. Another relates to obtaining the funding. However, of equal importance – especially when landscape scale change is involved – is how do you bring society along with you? Are you delivering what local communities want? Was there legitimate inclusion of stakeholders and end users and was there adequate consideration of their views? An important part of the PACCo initiative has been to capture all of the lessons from the delivery of the scheme in the Otter and Saâne valleys, and this has included undertaking a critique of the engagement undertaken.

The engagement story during the planning of LORP is long, lasting almost eight years until planning was achieved and the project in its final form could proceed. It began in 2009 when Clinton Devon Estates commissioned a report on the current drainage and flood management of the Lower Otter. This listed ten interventions, both small and large, for the Estate to consider and consult upon. Initial outreach outside of the Estate first occurred in 2013 and included a meeting which involved a local civil society organisation, the Environment Agency, Devon Wildlife Trust, South West Water, and East Devon District Council i.e. a mix of civil, statutory and local authority representation. At this meeting there was a unanimous view that it was worthwhile investigating a managed realignment approach in the Lower Otter valley.

What followed was a series of further early engagements with potentially impacted parties including the local cricket club and the local authority public rights of way team. Outreach then broadened from 2013 with articles on the subject and early proposals submitted to local community newsletters and newspapers. There has since been criticism that there was already a fairly strongly defined concept in mind at this point, before more extensive public consultation. This is probably a true observation, but any plans such as they were, were certainly ill-defined. In a sense, everything that was legal, fundable, technically possible and had landowner agreement was on the table for discussion. However, perhaps a stage was missed which was having reflective and non-directional discussions about the lower Otter valley to ascertain what the issues were (if any), as perceived by a broader group from local communities. Did they perceive the problems, and solutions, in the same way? That said, sometimes it is easier to present something as an idea for discussion and to begin a conversation. A number of times when early engagement was undertaken, the project team were requested to go away and come back when there was something more tangible to comment upon.

Further engagement followed thick and fast from 2014, including with local tenant farmers and the community of South Farm, with several public consultation events at local community centres advertised through signs on footpaths, at key community locations and through the local newspaper. Approximately 80 people attended these. It is true to say that a number of people were very troubled by and suspicious of the proposals. Concerns included flood risk, loss of wildlife and the loss, or at least change, of a cherished landscape. At this time project development was being undertaken by the Environment Agency and Clinton Devon Estates, two relatively large organisations, and it was perceived by some that there was a power imbalance with something ‘being done’ to local communities by powerful ‘outsider’ bodies. They wondered whether the engagement was genuine. Did they really have a voice? Could they really change anything?

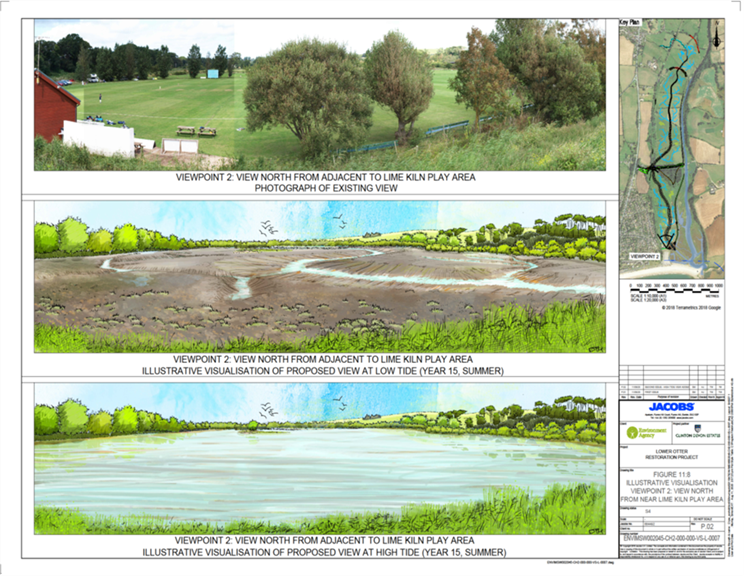

An independently chaired Stakeholder Group that included representation from local parish councils, local authorities, a local civil society group, several resident groups likely to be most impacted, the cricket club , the East Devon AONB and statutory agencies was convened from 2016 to help shape the project further, with a website established to present information about the scheme and act as a mechanism for receiving and responding to local views. An ‘issues log’ that included local concerns was also created. At this time the project team was also creating various graphic resources showing how the local landscape might change under the proposals. These documents also attempted to highlight the threats from climate change. Communicating this information was problematic, especially when many things were not certain (e.g. whether an embankment, may or may not be catastrophically breached at some point in the future; whether an agency may or may not decide to continue repairing local infrastructure including paths or roads at some unknown point in the future etc.).

A key gauge of local opinion came in 2017 when an options appraisal presenting a number of possible scenarios was presented to the public. The choice of options was shaped by the stakeholder group. Of the 144 people who attended the exhibition, the option taken forward to final delivery was the one that received the most support (62%). This event also received a lot of local press coverage, being reported in the Budleigh Journal, Devon Live, Express & Echo, and in a segment for BBC South West Spotlight.

After this event the project went into a period dedicated to trying to understand what was technically possible, the risks involved and where funding might come from. It is probably true to say that engagement lessened whilst answers were found to these important questions. Perhaps we were too quiet during this period and the conversation was allowed to slow, however, this period also coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic, so there were external constraints as well.

The final chance for people to comment was through the planning application which was validated in 2020 and which followed standard council procedures. The lodging of the application coincided with the creation of a campaign group to stop the project and significant social media traffic (both positive and negative). The planning application received 566 responses including 295 letters of support and 240 letters of objection. Clearly the community was divided on the matter, although the project was granted planning approval by a unanimous vote.

So, what can we learn from this process? Three simple easy lessons that come immediately mind are fairly obvious: consult early; take time to understand community perceptions about the issue that is trying to be addressed before developing initial ideas too far; treat engagement seriously and approach it honestly in ‘listening mode’; resource it as much as you can, as early as you can. Also, make sure that you cast your net as wide as possible so no particular group feels left out and voiceless. It is unlikely that one will ever achieve full consensus for a project of this kind, but following these simple lessons will give you the best chance. For LORP, the creation of a stakeholder group encompassing broad views was very positive.

To try and get an independent evaluation of the engagement undertaken, the project team commissioned Exeter University to scrutinize all materials related to the project engagement and also to create a model of ‘the best approach’. These reports are available on this website. This review concluded that there was a credible and transparent account of engagement, that a high level of integration was attained, with legitimacy increasing midway through the project in response to community feedback and when greater specialist resource deployed. However, it also concluded that the final plans remained largely consistent with the earliest visions. A conclusion that could be drawn from this is that there was limited ‘flex’ in the process to accommodate new ideas. It is also recommended that local knowledge and views should be collated and viewed alongside those of specialists.

The delivery of LORP has been a bumpy ride from an engagement and communication perspective. Views remain split on the project with significant tension between the project team and certain elements of the community at certain times. The lower Otter valley was much loved as it was and for many there was, and remains, a visceral sense of loss of the former landscape. It has also been difficult when the delivery of the project has involved significant disruption for extended periods, the clearing of pre-existing habitats and the Otter valley effectively turning into a giant building site whilst the project is delivered. During the delivery phase it has been of great value having dedicated staff whose sole function is to communicate with the public what is going on; making sure they have someone to speak to about their concerns.

And the best model of engagement? This can be found on the downloads section of this website and is consistent with a move from the (outdated) ‘Decide, Announce, Defend’ model (!) towards the ‘Engage, Deliberate, Decide’ model. It advocates that the engagement process ideally needs to be empowering of those involved and with adequate representation. Building trust is also viewed as vital to facilitate social acceptability of any proposed changes with the uncertainties related to climate change also accepted. It also advocates that every effort should be made to communicate and make accessible what are likely to be complex drivers and solutions with information shared through multiple methods. Finally, it advises that engagement should be early and sustained throughout the project lifespan and beyond. There are, of course, constraints to achieving this idealized approach, including its resourcing, limiting of true creativity due to technical constraints and legal, regulatory and funding requirements that might limit what it is possible for a project to deliver.

So, was engagement related to the delivery of LORP a success or not? This is for others to judge. However, I do believe that the project team did their best with the resources at their disposal and that this task was undertaken honestly. A huge effort was made. It certainly wasn’t easy and some of the conversations along the way were hard. It would have been easy to retreat and take on a bunker mentality but I hope this wasn’t the case. However you approach climate adaptation, I suspect the road will be tricky, certain conversations will be difficult and at times stressful and that the skin of those involved will have grown a little thicker by the end of it. Whatever you do you will not please everyone. I also believe that we have learnt a lot and yes, there were a few things I would have approached differently knowing what I do now. Learning from those mistakes is part of the point of PACCo.

An executive summary, including the engagement model as well as the two full engagement reports are available on the reports section of the downloads page on the PACCo website.